NCC: Going batty in BC

Early morning scene of a small town in Transylvania, Romania, while volunteering with Operation Wallacea, Romania chapter. (Photo by Katie Bell)

The moon is full and bright, with fog settled in the valley, making for an eerie view. It is early morning, just before sunrise. I am with a group of volunteers and one biologist. We are on our way back to camp after a two-hour walk around a small town in Transylvania, Romania, looking for bats. Yes, I helped study bats in the land of Dracula!

For one month in midsummer 2014, I participated in a biodiversity study with Operation Wallacea in Romania. Natura 2000 is a network of protected areas across Europe to conserve important medieval grasslands and associated habitat. As a research assistant, I helped monitor an array of species (butterflies, indicator plants, birds, small mammals and large mammals) to elucidate impacts of changes in farming practices on the biodiversity of these lands. To monitor bats, we would go out at dawn or dusk with acoustic devices to record echolocation sounds and determine species presence.

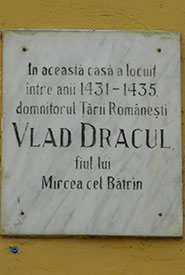

Romanian sign on building in Sighişoara, Transylvania that reads, “In this house between 1431-1435 lived the rule of the Romania country Vlad Dracul. Son of Mircea cel Bâtrin.” (Photo by Katie Bell)

Painting of Vlad Dracul inside the house. (Photo by Katie Bell)

Having returned to Victoria, BC, in 2015 with a new-found fascination for bats, I was in search of opportunities to help local bats. Why do the bats need help? Over six million bats have died across North America since 2006 as a result of white-nose syndrome (WNS). WNS is caused by a fungus that attacks hibernating bats in caves, when they are inactive and vulnerable. The fungus consumes the skin of bats’ mouths and wings, which causes them to wake from hibernation and use up limited fat reserves, eventually leading to death.

Little brown myotis exhibiting white-nose syndrome – note white fuzz on mouth and wings. (Photo by Marvin Moriarty)

This disease was first detected in a New York cave in 2006, introduced from Europe presumably on the gear and clothing of cavers. As the disease moves westward, it continues to devastate populations of bats in the U.S. and Canada. WNS kills 70 to 100 per cent of bats in a colony and is the worst wildlife disease outbreak in North America, to date. The little brown myotis, found throughout North America, has been particularly affected. It is considered endangered across Canada and is vulnerable to extinction globally.

In 2016, WNS was found in Washington state, again, likely a human-caused transmission event. The emergence of the disease on the West Coast set off alarm bells for biologists throughout BC, who had been watching the natural spread of the disease and had not anticipated its arrival for another few years.

Is the disease already here? Are we prepared to effectively manage local populations? To spread the word about the importance of bats (for natural insect control and nutrient cycling) and the impending arrival of WNS, and to establish baseline population numbers, local projects associated with the Community Bat Programs of BC started popping up across the province.

A central part of these programs is monitoring. Bats are counted as they exit a maternity roost, where females congregate to birth and raise young. Each roost is counted at least four times each summer: twice before pups (baby bats) are flying and twice after. Habitat Acquisition Trust (HAT) is responsible for the Community Bat Program on south Vancouver Island. Every summer since 2015, I have looked forward to volunteering with HAT to count bats. You never really know how an evening count will turn out.

In July, when counting a roost for the third time in summer 2020, we expected to count over 100 individuals, now that the pups were flying. Instead, there was great disappointment when a mere five individuals emerged. What was going on? Were the bats okay?

“Scccrreeecchhhhhh!”

What was that?

I heard a swoop near me.

Rocket box maternity roost in Elk/Beaver Lake Regional Park, Victoria, BC with informative sign (Photo by Katie Bell/NCC staff)

Barred owls perched on a nearby stump (Photo by Katie Bell/NCC staff)

An adult and two juvenile barred owls were calling and flying around, ready and waiting for their prey to emerge. The owls had found the local bat buffet. The bats (well, most of them), were not fooled — tonight was a great night to just hang out. Although limited in the number of bats that swooped overhead (as most did not emerge from the bat box), the presence of the owls made for an exciting encounter of predator-prey relationships at work. When we monitored the boxes for the fourth time that summer, the owls were nowhere to be seen and we counted 105 bats!

There are two bat boxes that stand (about 100 metres apart) near the Beaver Ponds at Elk/Beaver Lake Regional Park. During the five summers (2016-2020) that HAT has monitored these boxes, the data shows that different species cohabit the boxes and that individuals use both boxes, moving between the two in a given summer. These boxes are a great example of how supplementary habitat, when constructed properly, provide an effective home for females to raise young and, thus, support local bat populations.

Help your local bats

- Learn about why they are special and important.

- Volunteer at a bat count.

- Put a bat box on your property (but first, please reach out to your local bat conservation organization to make sure it is just right)

- Take the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Small Acts of Conservation: Be Batty challenge