Chronic fatigue syndrome a possible long-term effect of Covid-19, experts say

“I could barely raise my hand to hail a cab,” she said.

After nearly two years, Wilder was diagnosed with a disease called myalgic encephalomyelitis, also called chronic fatigue syndrome, a neuroimmune condition with symptoms including brain fog, severe fatigue, pain, immune aberrations and post-exertional malaise.

She had worked for decades as a social worker and activist for marginalized communities, focusing on HIV research and education programs and LGBTQ health. Wilder was shocked to find that ME/CFS lacked a drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and scientists studying the disease only received about $5 million annually in research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

At that point, she found herself in an altogether new marginalized disease community, reminiscent of the stigmatized groups she fought for at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

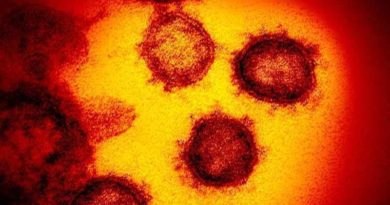

A chronic disease, ME/CFS can last for decades. It often takes root following some form of viral infection, for instance Epstein-Barr virus or Ross River virus. The novel coronavirus is just one more virus that can potentially trigger the onset of this debilitating condition.

Wilder fears that hundreds of thousands of people with Covid-19 could develop the same illness plaguing her. And leading medical experts have the same concern.

“It’s extraordinary how many people have a postviral syndrome that’s very strikingly similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.”

Many are falling ill and staying ill

More than six months into the global coronavirus crisis, many who contract Covid-19 are not fully recovering.

Up to 35% of those diagnosed with Covid-19 were not back to their normal selves two to three weeks after testing positive for the coronavirus, according to a July 24 report by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 292 people the CDC surveyed on post-Covid recoveries, those recovering from Covid-19 reported a median of seven of the CDC’s 17 symptoms.

One of those still struggling with symptoms months later is CNN anchor Chris Cuomo, who first announced that he tested positive for the coronavirus on March 31.

“I’ve got brain fog that won’t go away,” Cuomo said. “I’ve got an onset of clinical depression, which is not sadness. People keep saying to me, ‘Don’t be sad.’ I’m not sad. I’m depressed. It’s different. I can’t control it.”

Cuomo has regularly talked on air about his battle with Covid-19, and he’s conversed with viewers on Twitter about his journey, many of whom say their Covid-19 symptoms are lingering, too.

“I can’t recover from workouts the way I did before,” he continued.

If you have chronic Covid-19, it’s important to rest

Living with ME/CFS, seeing Covid-19 pillage her city and reading press reports of Covid-19 patients not recovering has left Wilder on edge.

She has been using all her connections from her career in public health to help raise the alarm about chronic symptoms that so-called Covid “long-haulers” are likely to face for months or years to come.

“The first thing that terrifies me is ‘Don’t exercise.’ You can make yourself sicker,” Wilder said. “This is something that everyone with ME wishes that somebody had told them in advance. We don’t want people to go through the things that we did.”

Those with ME/CFS should prioritize activity management, or pacing, the CDC recommends. This means you should understand your physical and cognitive limits, and not push beyond them, as this will result in a crash, setting you back on your recovery. “Some patients and doctors refer to staying within these limits as staying within the ‘energy envelope,'” the agency said.

Researchers are monitoring how patients’ symptoms progress

A number of research and support groups are setting up to help people struggling with long-term Covid-19 symptoms and to explore how and why immune system abnormalities might lead to ME/CFS.

Members of Congress are taking notice as well.

The group launched a study of Covid-19 patients that will monitor how their disease and its possible aftereffects, specifically chronic conditions that might occur after an illness, evolve. The researchers will analyze patients’ genomes, as well as complete protein and metabolism profiles at regular intervals.

“Covid-19 gives us an unprecedented opportunity to advance our understanding of post-viral disease,” said Dr. Ami Mac, the director of translational medicine at the Stanford Genome Technology Center, which is associated with the OMF.

“This could result in a longstanding public health disaster leaving in its wake untold numbers of new sufferers of a condition that feels like a ‘living death’ for those of us afflicted,” Mac, who has ME/CFS, said.

In the next couple weeks, she hopes to finish building an app by which researchers can follow Covid-19 patients and the symptoms, tracking how and when they develop symptoms consistent with ME/CFS.

“We plan to obtain blood samples over a few years longitudinally to allow us to see which molecular changes occur that prevent resolution of symptoms,” she said.

Both Mac and Wilder plan to keep dedicating themselves as strong advocates for Covid-19 long-haulers who need all the support, scientifically and socially, that they can get.

One way Wilder did that was by asking Fauci a question about ME/CFS and Covid-19 at a July 9 news conference organized by the International AIDS Society.

Fauci’s acknowledgement of the link garnered international headlines, and afterwards he went on to compare the two conditions publicly on at least two other occasions last month.

“Because of my HIV background and my knowledge of social activist groups like Act Up, I just quickly realized we have to work together and I have to take advantage of every opportunity available to me,” Wilder said.