COVID-19 Is Revealing Problems With How Hawaii’s Government Uses Data

COVID-19 has exposed structural problems in not only how the Hawaii Department of Health collects and shares its data, but how government officials approach data in general.

“This pandemic just shows you the historic deficiencies in the system,” said Victoria Fan, a health economist and professor at the University of Hawaii whose team was enlisted by the state to work on its new COVID-19 data dashboard.

The Department of Health, which set up a command center for contact tracing at the Hawaii Convention Center earlier this summer, was struggling with outdated equipment, including the use of a fax machine for collecting reports.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

These deficiencies include the lack of enough staff who know data science, underpaid and overworked public servants and outdated systems that are incapable of handling modern-day problems, she said.

Take the fax machine debacle, she said, pointing to a revelation in early September that a major challenge for contact tracing was the need to scan and input information faxed by doctors.

The health department has also been unwilling to disclose certain data, often citing privacy concerns, and has been unwilling to cooperate with outside organizations in multiple instances.

That seems to be changing under new leadership, including a new director of the health department and a new head of its disease investigations division

“They’re already making efforts to provide some of the data that we need,” said Carl Bonham, executive director of the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization and a member of the Hawaii House Select Committee on COVID-19 Economic and Financial Preparedness.

Emily Roberson took over the contact tracing program in July.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

There is also more willingness to collaborate, Fan said. For example, the new state dashboard that she and her team at UH are working on is a collaboration between DOH and multiple agencies, sourcing data from Hawaii Data Collaborative, Hawaii Emergency Management, the Hawaii Pandemic Applied Modeling Work Group and others.

“This pandemic is so much bigger and so much more complex than anything else we have dealt with in the past,” said Dr. Janet Berreman, the health department’s district health officer for Kauai who is in charge of directing the new data dashboard. “We really can’t do this with the business as usual approach and the way forward is for us to join hands.”

For there to be better data collection and sharing — not only at the health department but across the state government — there needs to be fundamental changes, including building a pipeline of data scientists who understand the system, Fan said. They are going to be the ones who can negotiate for a better infrastructure and do better analysis.

“It’s about humans and the workforce,” she said. “It’s not just about the numbers you can crunch today.”

What Went Wrong

In the first six months of the pandemic, the state Department of Health withheld a lot of essential data about the virus from the public — and even policymakers — prompting an outcry for more transparency and disclosure.

It took five months to get racial breakdowns of COVID-19 deaths in the state, and six months to get an accurate number of contact tracers investigating cases.

“We are still in a situation today where we don’t have the data flowing that we need to effectively manage the crisis,” said Nick Redding, executive director of the Hawaii Data Collaborative, a nonprofit organization working to boost data in the state.

But this is not just the health department’s problem, he said.

“At some point, we have to stand back from DOH as the villain and really reflect on what made where we are today probably inevitable given the culture around data in the state — the culture that permeates how government agencies work,” he said.

There doesn’t seem to be a clear data strategy for the virus response, and no evidence that data is being used in policymaking. Thus far in the pandemic, city and state officials have taken heat for measures that some say “defy science.”

“There’s a glaring disconnect between what the data says and how that informs decisions,” he said.

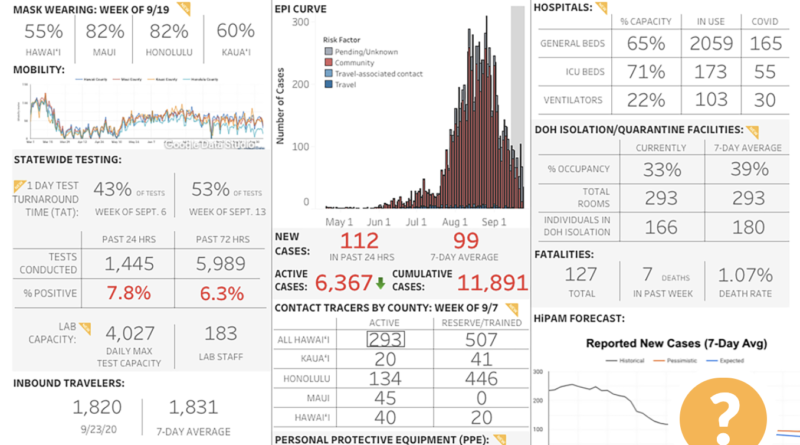

The new data dashboard that Victoria Fan and her team are building is supposed to be the link between data and policy by providing the most important data about COVID-19, Berreman of DOH said. The dashboard, which launched as a static prototype on Sept. 4, includes a dozen essential indicators that were selected based on recommendations by the international public health organization Resolve to Save Lives in four specific areas — prevention, detection, containment and treatment.

“The utility of the data is to inform all the moving pieces and give a full picture,” she said.

The dashboard helped boost Hawaii’s data grade from the COVID Tracking Project. It went from a D to a B, despite it still being a prototype.

The dashboard launched as a static prototype on Sept. 4. As of Tuesday, the dashboard is interactive.

Screenshot-Hawaii Covid-19

The dashboard, which contains data from multiple sources, required the collaboration of multiple agencies and groups, Berreman said. That may not have happened under previous leadership.

“It’s a huge shift from DOH saying we’re not going to give you any data to here, we want you to build this dashboard,” Fan said.

What is Fault Lines?

“Fault Lines” is a special project that explores disruption and discord in Hawaii and what we as a community can do to bridge some of the social and political gaps that are developing. Read more here.

The House COVID-19 committee was one of the entities applying pressure on the health department to produce more data. Its subcommittee created an alliance to develop and launch another data dashboard with a storytelling component called Covid Pau.

“The data stuff has been a moving target,” said Na‘alehu Anthony, a filmmaker who also serves on the House committee. “We have this direct tie to how good the data is to how good the response can be.”

As much as possible, the state and health department should make granular data available so that policymakers can create more tailored decisions, he said.

Cautious Optimism

Lawmakers and researchers are still asking for more information about the COVID-19 response. And there have not been the broader conversations about structural reforms to the data infrastructure of the state government that Redding and others say is needed.

“Where we are today, I still don’t think we are taking data seriously,” Redding said.

Nick Redding is the executive director of the Hawaii Data Collaborative.

Nick Redding

Completing the new data dashboard would be a good first step, he said.

The new dashboard is still missing data on timeliness of case and contact interviews — something the health department has promised to release.

Emily Roberson, the head of disease investigations, said her division could not yet provide performance metrics for contact tracing because the team is still analyzing data to ensure its accuracy before publishing.

The investigation branch changed the way it evaluates and monitors data, so it will require some extra calculations, she said. Going forward, more information will be collected about how successful they are in reaching people who have tested positive, as well as their contacts, she said.

Bonham of UHERO says he and the committee are going to continue to push for data, because the state needs it to make decisions about reopening.

Like others, Bonham is optimistic that changes in leadership at the health department will lead to more transparency.

“The question is whether changes in leadership is enough, right?” he said. “There’s whole cultures and bureaucracies that have to be dealt with.”

The state’s data dashboard that Victoria Fan and her team at UH worked on became interactive on Sept. 29.

This pandemic has shown that the state needs to figure out how to build a stronger higher-performing health department, Fan said. There are a lot of reforms that are needed, including an overhaul of the systems and infrastructure, and a recalibration of how people think about the role that data plays in the public health system.

“In the end it’s about the people at the Department of Health and whether they have the capacity to do data science,” she said. “And they really should.”

Civil Beat Health Reporter Eleni Avendaño contributed to this story.