COVID-19: What went wrong in Utah? Analyzing missteps, looking forward

SALT LAKE CITY — It’s been nearly five months since everything changed and Utahns started dying from the new coronavirus.

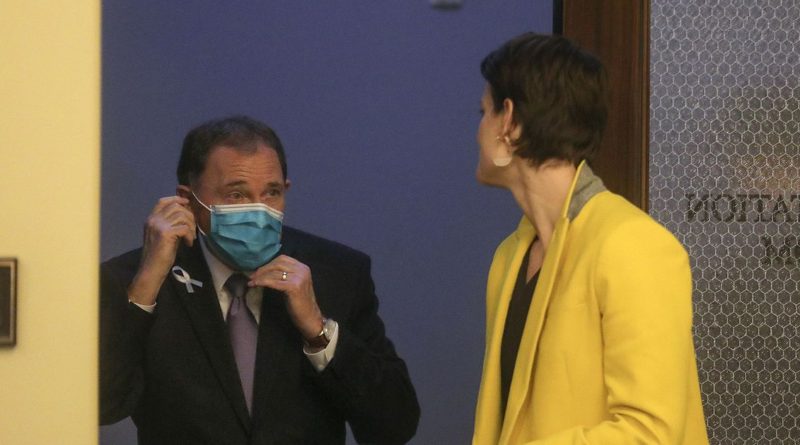

Ever since Gov. Gary Herbert declared Utah’s COVID-19 state of emergency on March 6, government leaders have continued to scramble to stem the pandemic — all while caught in a storm of polarized opinions over government mandates that have become increasingly politicized.

As the surge in COVID-19 cases continues, so do frustrations over Utah’s — and the nation’s — so far unsuccessful efforts to bring the pandemic under control.

The Deseret News spoke with medical experts with epidemiological backgrounds to analyze Utah’s overall COVID-19 response, and while those experts credit state leaders with starting off on the right foot by enacting swift shutdowns to stop the spread of COVID-19, they say the state’s approach to reopening has left the public with confusing and mixed messages about the continued dangers of this contagious disease.

State officials have tried to use innovation to combat the virus, but that innovation hasn’t worked out as planned. And at times, controversy has stirred over those public-private partnerships and whether they were appropriate.

From questions around an early purchase of anti-malarial drugs that was later refunded, to issues around the TestUtah initiative and the Healthy Together app, state officials acknowledge missteps, but they say it’s unrealistic to expect government to be perfect while responding in an emergency.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20097224/merlin_2824092.jpg)

To state leaders, they view their overall COVID-19 response as a balancing act: one to weigh public health with economic health, and they argue they’re striking that balance, pointing to Utah’s low COVID-19 fatality rate and low unemployment rate compared to other states in the nation.

But to some medical health experts, the balancing approach is misguided because, they contend, economic health cannot come until there is public health.

“Things have been framed incorrectly from the get-go,” said Dr. Andrew Pavia, chief of pediatric infectious disease at the University of Utah, lamenting the now hyperpoliticized climate around mask mandates and economic closures.

“It’s not a question of health versus the economy. It’s a question of health in order to make the economy work.”

Pavia also worries that in their balancing act, state officials haven’t properly balanced medical advice in their decision-making on a variety of issues, whether it be their approach to economic re-openings, reluctance to issue a statewide mask mandate, or multimillion-dollar, no-bid contracts with tech companies pitched as innovative ways to respond to the pandemic.

“Many decisions were made without consulting the medical experts,” Pavia said, pointing to an early purchase (which was later refunded) of anti-malarial drugs that went against concerns raised by many Utah health experts and the state’s own epidemiologist, Dr. Angela Dunn.

“Often Dr. Dunn’s recommendations were ignored. … Infectious disease experts were not listened to,” Pavia said. “That’s true of hydroxychloroquine, that’s certainly true for the inconsistent messaging about masking. … Now we see the disease is spreading everywhere in the state.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20097225/merlin_2824094.jpg)

Health ‘at the table’

Dunn, in an interview with the Deseret News on Friday, said Gov. Gary Herbert has involved public health experts like herself in decision-making around reopenings and masking, but she wasn’t involved in decisions made by the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget to enter into now controversial no-bid contracts with tech companies on initiatives like TestUtah, the Healthy Together app, or the purchase of hydroxychloroquine.

As for the decisions she did have a seat at the table for, Dunn said she doesn’t feel like she’s been ignored, and understands state leaders like Herbert have to make tough calls while considering information from many different angles.

“My role is to provide state leadership with scientific evidence, and it’s up to them to decide how they weigh all the different recommendations coming at them. That’s definitely the hardship of being an elected official,” she said. “This is the first pandemic we’ve all been through, so we’re certainly learning as we go. But health has been at the table.”

Asked if she believes state leaders have put enough weight on medical expertise when making decisions, Dunn said that isn’t up to her to decide.

“How the governor chooses to run a statewide pandemic response is definitely his choice and his authority, and I have to respect that as a state employee and department of health employee,” Dunn said. “I see my job as to make sure state leadership has the science and the data and understanding so they can make the best decisions that are able to be made.”

To Dunn, now it’s a matter of individual Utahns making smart choices — wearing masks, prioritizing social distancing and staying home when sick.

“We are all a part of the solution. We shouldn’t have to depend on the government making mandates or forcing us to do something,” Dunn said. “So I think we just need to move the conversation away from a blame game to ‘We are all part of the solution,’ and we should take ownership of that.”

As the state remains caught in the middle of the COVID-19 firestorm — 760 new cases of the novel coronavirus and eight more deaths reported on Saturday — critics like Pavia and Democratic lawmakers hope state leaders will change their approach, learn from mistakes made, and rely more heavily on medical expertise as they continue to make decisions.

But legislative leaders like House Speaker Brad Wilson — though he acknowledges mistakes have been made along the way — defend Herbert and his staff, saying they have in fact made decisions with public health expertise at the forefront, balancing those with a need to prevent disastrous impacts on the state’s economy.

“I know Gov. Herbert very well, and I can tell you with 100% certainty that his style is to gather as much information from as many people as possible, and then make a decision,” Wilson, R-Kaysville, told the Deseret News, dismissing any criticism that Herbert hasn’t been listening to medical advice. “I think that’s a crock. I don’t believe that at all. I believe he’s taken his feedback from all kinds of sources and then made his decisions.”

Wilson said Dunn or other health officials are often, if not always, in the room, and if they’re not, “they’re spoken of fondly and their information and perspective is very well regarded.”

Above all, Utah Senate President Stuart Adams, R-Layton, said government officials are “trying their best,” and “every decision you make as a policymaker must be with a holistic approach.”

Asked whether the state has appropriately weighed medical expertise and economic decisions, Adams said, “Time will tell.”

“I hope we have,” he said. “But right now I think 20/20 hindsight will give us a lot more information than we have. … Whether we have or not we will probably know in six months.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20087963/merlin_2823916.jpg)

Balancing act

Herbert’s office this week did not respond to multiple requests for an interview for this story. Kristen Cox, executive director of the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, was not available for an interview, according to her spokesman, but the office answered Deseret News questions via email.

“Utah has the lowest COVID-19 case fatality rate and has the second-lowest unemployment rate in the nation — dropping from 8.6% in May to 5.1% in June,” the response from the budget office states. “Our goal throughout the entire COVID-19 response has been a balanced approach between protecting lives and livelihoods, and it will continue to be so. A strong economy and a healthy public are inextricably linked. Those hit hardest by the economic fallout of the pandemic are also those hit hardest by this public health crisis.”

On a nationwide scale, Utah remains among the states with the lowest COVID-19 death rates, with 235 total deaths amid 32,572 positive cases as of Friday, according to the Utah Department of Health.

The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget also wrote Utah’s response has “continually relied on experts from both the medical and economic community, and will continue to do so.”

In addition to using Goldratt Consulting, a business consulting firm to guide decision making, the management and budget office said state officials have also “relied on public health and operational expertise” from the Utah Department of Health; the health care intelligence firm Leavitt Partners; the University of Utah HERO Project, a medical panel; “and a data analytics team made up of experts from the state’s hospitals and health departments.”

The state’s recent surge in cases has put Utah on the national map, included in a list of 18 states that a document prepared for the White House Coronavirus Task Force labels as in a “red zone” for COVID-19 cases. The document suggests those states, including Utah, should return to more stringent protective measures, limit social gatherings to 10 people or fewer, close bars and gyms, and ask residents to wear masks at all times, according to a report by the Center for Public Integrity.

Asked about the surge and what mistakes state officials are learning from, the office said “recent data indicate that the rate of positive COVID-19 cases is beginning to plateau.”

“Nonetheless, the state is watching these numbers closely and is working with leadership from the state’s hospitals to understand their surge capacity and ensure there are enough beds for those who need care as the state works to drive down positive cases.”

The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget also outlined a list of successes amid the pandemic, from declining business outbreaks, a declining case fatality rate, the percent of hospitalizations declining, “public attitudes toward masks and social distancing are becoming more supportive overall,” and decreasing unemployment rate. The office also included a list of “ambitious targets” it is working with the Utah Department of Health to improve, including testing result turnaround and swifter response to outbreaks in long-term care facilities and worksites.

“The results speak for themselves,” the office wrote, again referring to the state’s low fatality and unemployment rates. “While there is much work to be done, Utah is doing a good job at threading the needle of protecting lives and livelihoods.”

Color-coded mistakes

To former state epidemiologist Dr. Robert Rolfs, the state’s response began on the right foot, but since then has struggled with sending clear messages to Utahns that the pandemic is a serious threat, now more than ever.

“I thought the state did well by closing early. I agreed with reopening, but not how it was done,” Rolfs said, adding that state leadership’s messaging about different areas being in red, orange, yellow, and green risk levels was “poor and confusing” and “should have been phased to allow detection of the results because of the lag between behavior and cases.”

“The risk scale has been used largely disregarding actual risk,” Rolfs said. “As a result, cases have increased three- to four-fold.”

Rolfs, while he said he is “reluctant to be critical of officials who are managing an outbreak that has not been easy to predict,” said he can’t anticipate Utah’s trajectory. But if trends continue, hospitals could be overwhelmed and doctors could be put in impossible situations.

“I don’t know the future,” he said. “It is possible that transmission will level off at a sustainable level (accepting that this means deaths, especially of vulnerable people including elderly and essential workers). However, I am concerned that the trend will continue upward with serious consequences.

“I believe we need to act now before that happens with both mask use and reduced gathering of people — hopefully in ways that have less economic impact.”

Pavia agrees that the state started off “very much on the right foot” by taking early and definitive actions for closures and encouraging Utahns to stay home.

But since then? Pavia said stopping short of issuing a statewide mask mandate and advertising certain areas as being “low risk” while opening up the economy has confused and placated the public to the pandemic’s real risks.

“Unfortunately, I think we have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory,” Pavia said.

While Herbert has allowed local jurisdictions like Salt Lake and Summit counties to enact their own mask mandates and has been verbally supportive of Utahns wearing masks, Pavia said a statewide mask mandate would send a clearer and important message to Utahns about the need to wear face coverings.

Pavia also believes the state’s approach to economic reopenings have been a contributing factor to the state’s surge in cases.

“We needed to begin a smart economic reopening, but what we ended up doing was a wholesale reopening of risky behavior,” he said.

Missteps

To House Minority Leader Brian King, D-Salt Lake City, as he’s watched state officials navigate the COVID-19 chaos, he sincerely believes “everybody’s trying the best that they can.”

“But good intent is not a substitute for really being careful and competent,” he said. “And sometimes, I think obviously we’ve made mistakes. Nobody’s questioning that — nobody in their right mind questions that. There are going to be mistakes made, partly because we don’t understand the disease as much as we’d like to and need to.”

Early on, one of the first issues that alarmed medical experts was state officials’ interest in purchasing hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, at the time drawn in by hype about a possible drug to treat COVID-19, touted by President Donald Trump.

But health experts’ opinions about the drugs were far from consensus. And even as many doctors cautioned state officials against using the unproven drug for COVID-19, emails show health department director Dr. Joseph Miner and deputy director Dr. Marc Babitz were early backers of an initiative to distribute the drugs first pitched by tech CEO Mark Newman, pushed by Utah pharmacist Dan Richards, who stockpiled the drugs, and egged on by Dr. Kurt Hegmann, a University of Utah physician specializing in preventive, occupational and environmental medicine.

Emails show that Dunn, who has become a high-profile public face in the state’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic, was also at odds with her bosses over the use of the anti-malarial drugs. But days after the plan for a standing order to allow distribution of the drugs fizzled, the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget green-lighted an $800,000 purchase of 20,000 courses of the drug, which was later refunded days after it came to light, with state leaders blaming the purchase on “breakdowns of communication between state agencies.”

In April, Paul Edwards, communications director of the state’s COVID-19 Community Task Force, said the order was authorized by the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget after the governor’s administration “empowered” that office early on in its pandemic response to make “quick, strategic decisions to support the state’s response to the pandemic.”

The governor’s office completed a quick internal review of the purchase and determined “all involved acted in good faith,” but details around how those breakdowns occurred and what prompted the management and budget office to move forward with the purchase are still murky.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19918484/merlin_2774875.jpg)

No-bid contracts

State leaders have said that during that time, officials were responding in a chaotic and uncertain situation. During those months, Utah spent more than $108 million on emergency procurement purchases, much of which was for bulk personal protective equipment, unconstrained by usual competitive bidding requirements that had been suspended amid the emergency.

Those purchases allowed Utah to get ahead with its stock of masks, gloves and gowns, but some lawmakers were alarmed by how quickly more than $100 million was spent, and that spurred them to seek more transparency and checks to the state’s emergency procurement powers.

During that time, state officials also entered into millions of dollars in no-bid contracts, some of which included partnerships with tech companies like Newman’s Nomi Health, which was originally pitched as one that would be crowdfunded.

That $5 million-plus contract became the TestUtah initiative, which included $2 million for the creation of TestUtah.com, $3 million for the first month of five drive-thru testing locations and lab services, and an additional $600,000 a month for each active testing location.

That contract, in particular, spurred questions about how state officials balanced the protection of the taxpayer dollar while responding in real time to the pandemic. Critics, like Lauren Simpson, Alliance for a Better Utah’s policy director, called it a “slapdash deal with tech groups” that “gave inexperienced, unelected and unaccountable private entities control over key parts of our state’s response to this public health crisis.”

Questions have also been raised about TestUtah’s testing accuracy, though MountainStar lab officials have vehemently defended their testing’s integrity, decrying what they deemed “undue scrutiny” in what they question was a “competitor-driven issue” with competing Utah labs.

State officials and Newman have defended the TestUtah initiative as one that, while not perfect, has become a valuable part of the state’s response to COVID-19, particularly to increase testing capacity. And a spokeswoman for the governor has said they never expected Nomi to provide their services free of charge.

“All of these ideas and programs were put in place to help stop the pandemic,” Wilson said. “And of course they had their pros and cons, but I’ll tell you right now, if we didn’t have TestUtah, we would be in a world of hurt. I have zero regrets about starting TestUtah. They went through a learning curve, but it is critical for us to get test turnaround in the state, and they’re returning tests faster than anybody else.”

After TestUtah’s 60-day contract expired, the Utah Department of Health put the contract out for bid. An independent selection team has reviewed those bids and is in the process of negotiating contracts with the successful bidders, according to the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget. In the meantime, the original contract was extended through August to ensure that the state wouldn’t lose any testing capacity during the bid process.

Wilson and Adams both said in interviews with the Deseret News this week that the state must focus on speeding up test results. Adams said he wants to see all test results be provided within 24 hours — though he doesn’t have specifics of how to get there. Adams and Wilson said that’s a work in progress.

Vastly overpaid?

Another no-bid contract that has raised questions is a more than $6 million contract with the tech firm Twenty to build the Healthy Together app, which was initially pitched as one that would help Utah track the spread of COVID-19 through contact tracing.

That feature of the app has languished amid what health officials have attributed to privacy concerns from the public. Earlier this month the app’s location services feature was turned off.

Some lawmakers, like Rep. Andrew Stoddard, D-Sandy, and Rep. Suzanne Harrison, D-Draper, who have both been outspoken critics of the state’s early response to COVID-19 and the millions spent in no-bid contracts to tech firms, have deemed the app a dud, and believe the state has “vastly overpaid.”

Though state officials months ago ended emergency procurement powers and reverted back to competitive bidding processes, the Twenty contract has continued. That’s despite the fact that state officials were approached days after they entered into the contract by another company, which offered contact tracing technology for free.

Now state officials are conversing with Taymour Semnani, CEO of Ferry, about his offer. But he has been puzzled why it’s taken so long for state officials to take his offer seriously. He said he still hopes state officials will figure out a way to integrate the technology, calling it a “powerful tool” to help fight the virus.

Wilson, asked about these contracts and their hiccups, said it’s unrealistic to expect everything to work perfectly, especially amid the ever-changing pandemic.

“The private sector tries things all the time to fix problems,” he said. “The difference is, when you stub your toe, it doesn’t end up on the news. We expect government to be perfect in everything when it’s trying new things. And that’s a pretty unrealistic expectation. We’re going to try new things, and some will work and some won’t.”

The contracts have raised questions about decision-making happening within the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget. King said he worries there has been too much “defensiveness” and not enough transparency and accountability of those contracts as they continue to be scrutinized by the public and the media.

“As long as people are acting in good faith and as long as they are reasonably responding to good, fact-based information and recommendations of public health and medical professionals, I’ll cut them some slack,” King said. “But we need to have great transparency so everyone has access to the information that allows everyone to evaluate how they’ve been performing. Only by having full transparency and disclosure are we in a good position … to look at what has worked and what is not working.”

Asked about more specifics for the chain of command on the hydroxychloroquine decisions — as well as no-bid contracts — the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget said in an email: “These decisions were made and directed through a multi-agency effort, including the Utah Department of Health, the governor’s office, the Department of Technology Services, and the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget.

“This is the first pandemic the state has battled in recent history, and we are sometimes learning as we go.”

State Auditor John Dougall is in the midst of a statewide audit of the state’s response thus far to COVID-19, meant to evaluate everything from the timeline of the state’s overall response, as well as issues including hydroxychloroquine, no-bid contracts and the millions spent on emergency procurement.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20097235/merlin_2824080.jpg)