Growing Data Show Blacks And Latinos Bear The Brunt Of COVID-19 : Shots

A medical professional administers a coronavirus test at a drive-thru testing site run by George Washington University Hospital, on May 26, 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

A medical professional administers a coronavirus test at a drive-thru testing site run by George Washington University Hospital, on May 26, 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

In April, New Orleans health officials realized their drive-through testing strategy for the coronavirus wasn’t working. The reason? Census tract data revealed hot spots for the virus were located in predominantly low-income African-American neighborhoods where many residents lacked cars.

In response, officials have changed their strategy, sending mobile testing vans to some of those areas, says Thomas LaVeist, dean of Tulane University’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and co-chair of Louisiana’s COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force.

“Data is the only way that we can see the virus,” LaVeist says. “We only have indicators. We can’t actually look at a person and tell who’s been infected. So what we have is data right now.”

Until a few weeks ago, racial data for COVID-19 was sparse. It’s still incomplete, but now 48 states plus Washington D.C., report at least some data; in total, race or ethnicity is known for around half of all cases and 90% of deaths. And though gaps remain, the pattern is clear: Communities of color are being hit disproportionately hard by COVID-19.

Public health experts say focusing on these disparities is crucial for helping communities respond to the virus effectively — so everyone is safer.

“I think it’s incumbent on all of us to realize that the health of all of us depends on the health of each of us,” says Dr. Alicia Fernandez, a professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, whose research focuses on health care disparities.

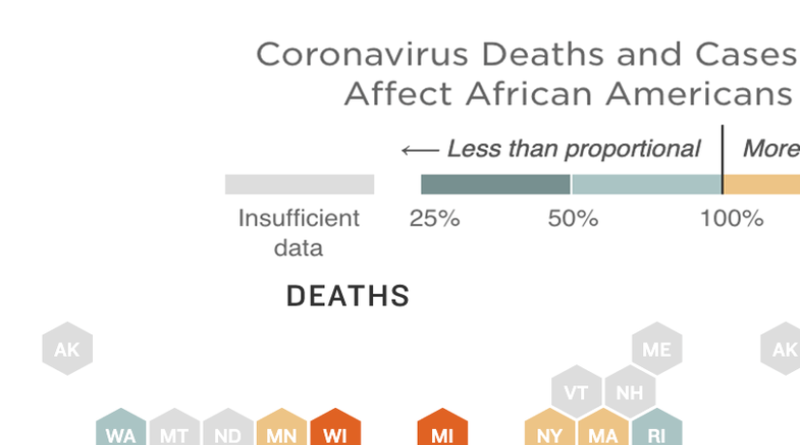

NPR analyzed COVID-19 demographic data collected by the COVID Racial Tracker, a joint project of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center and the COVID Tracking Project. This analysis compares each racial or ethnic group’s share of infections or deaths — where race and ethnicity is known — with their share of population. Here’s what it shows:

- Nationally, African-American deaths from COVID-19 are nearly two times greater than would be expected based on their share of the population. In four states, the rate is three or more times greater.

- In 42 states plus Washington D.C., Hispanics/Latinos make up a greater share of confirmed cases than their share of the population. In eight states, it’s more than four times greater.

- White deaths from COVID-19 are lower than their share of the population in 37 states and the District of Columbia.

Major holes in the data remain: 48% of cases and 9% of deaths still have no race tied to them. And that can hamper response to the crisis across the U.S., now and in the future, says Dr. Utibe Essien, a health equity researcher at the University of Pittsburgh who has studied COVID-19 racial and ethnic disparities.

“If we don’t know who is sick, we’re not going to know in six months, 12 months, 18, however long it takes, who should be getting the vaccination. We’re not going to know where we should be directing our personal protective equipment to make sure that health care workers are protected,” he says.

A heavy toll of African-American deaths

NPR’s analysis finds that in 32 states plus Washington D.C., blacks are dying at rates higher than their proportion of the population. In 21 states, it’s substantially higher, more than 50% above what would be expected. For example, in Wisconsin, at least 141 African Americans have died, representing 27% of all deaths in a state where just 6% of the state’s population is black.

“I’ve been at health equity research for a couple of decades now. Those of us in the field, sadly, expected this,” says Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, director of the Equity Research and Innovation Center at Yale School of Medicine.

“We know that these racial ethnic disparities in COVID-19 are the result of pre-pandemic realities. It’s a legacy of structural discrimination that has limited access to health and wealth for people of color,” she says.

African-Americans have higher rates of underlying conditions, including diabetes, heart disease, and lung disease, that are linked to more severe cases of COVID-19, Nunez-Smith notes. They also often have less access to quality health care, and are disproportionately represented in essential frontline jobs that can’t be done from home, increasing their exposure to the virus.

Data from a recently published paper in the Annals of Epidemiology reinforces the finding that African-Americans are harder hit in this pandemic. The study from researchers at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research, looks at county-level health outcomes, comparing counties with disproportionately black populations to all other counties.

Their analysis shows that while disproportionately black counties account for only 30% of the U.S. population, they were the location of 56% of COVID-19 deaths. And even disproportionately black counties with above-average wealth and health care coverage bore an unequal share of deaths.

“There’s a structural issue that’s taking place here, it’s not a genetic issue for all non-white individuals in the U.S.,” says Greg Millett, director of public policy at amfAR and lead researcher on the paper.

Hispanics bear a disproportionate share of infections

Latinos and Hispanics test positive for the coronavirus at rates higher than would be expected for their share of the population in all but one of the 44 jurisdictions that report Hispanic ethnicity data (42 states plus Washington D.C.). The rates are two times higher in 30 states, and over four times higher in eight states. For example, in Virginia more than 12,000 cases — 49% of all cases with known ethnicity — come from the Hispanic and Latino community, which makes up only 10% of the population.

Fernandez has seen these disparities first-hand as an internist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. While Latinos made up about 35% of patients there before the pandemic, she says they now make up over 80% of COVID-19 cases at the hospital.

“In the early stages, when we were noticing increased Latino hospitalization at our own hospital and we felt that no one was paying attention and that people were just happy that San Francisco was crushing the curve,” she says. “It felt horrendous. It felt as if people were dismissing those lives. … It took people longer to realize what was going on.”

People get free COVID-19 tests without needing to show ID, doctor’s note or symptoms at a drive-through and walk up Coronavirus testing center located in Arlington, Va., on May 26th.

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

People get free COVID-19 tests without needing to show ID, doctor’s note or symptoms at a drive-through and walk up Coronavirus testing center located in Arlington, Va., on May 26th.

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

Like African-Americans, Latinos are over-represented in essential jobs that increase their exposure to the virus, says Fernandez. Regardless of their occupation, high rates of poverty and low wages mean that many Latinos feel compelled to leave home to seek work. Dense, multi-generational housing conditions make it easier for the virus to spread, she says.

The disproportionate share of deaths isn’t as stark for Latinos as it is for African-Americans. Fernandez says that’s likely because the U.S. Latino population overall is younger — nearly three-quarters are millennials or younger, according to data from the Pew Research Center. But in California, “when you look at it by age groups, [older] Latinos are just as likely to die as African-Americans,” she says.

Other racial groups

While data for smaller minority populations is harder to come by, where it exists, it also shows glaring disparities. In New Mexico, Native American communities have accounted for 60% of cases but only 9% of the population. Similarly, in Arizona, at least 136 Native American have died from COVID-19, a striking 21% of deaths in a state where just 4% of the population are Native American.

In several states Asian Americans have seen a disproportionate share of cases. In South Dakota, for example, they account for only 2% of the population but 12% of cases. But beyond these places, data can be spotty. In Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Oklahoma and Wisconsin, Asian Americans and Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders are counted together, making comparison to census data difficult.

Fernandez points out that if COVID-19 demographic reporting included language, public health officials might see differences among different Asian groups, such as Vietnamese or Filipino Americans. “That’s what’s going to allow public health officials to really target different communities,” she says. “We need that kind of information.”

Understanding the unknowns

Months into the pandemic, painting a national picture of how minorities are being affected remains a fraught proposition, because in many states, large gaps remain in the data.

For instance, in New York state — until recently the epicenter of the the U.S outbreak — race and ethnicity data are available for deaths but not for cases. In Texas, which has a large minority population and a sizable outbreak, less than 25% of cases and deaths have race or ethnicity data associated with them.

There are also still concerns about how some states are collecting data, says Christopher Petrella, director of engagement for the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University. For example, he says West Virginia, which claims to have race data for 100% of positive cases and 82% of deaths only reports three categories: white, black and “other.”

Also some states appear to be listing Hispanics under the white category, says Samantha Artiga, director of the Disparities Policy Project at Kaiser Family Foundation,

“There’s a lot of variation across states in terms of how they report the data that makes comparing the data across states hard, as well as getting a full national picture,” Artiga says.

But experts fear that the available data actually undercounts the disparity observed in communities of color.

“I think we have the undercount anyway, because we know that minority communities are less likely to be tested for COVID-19,” says Millett. NPR’s own analysis found that in four out of six cities in Texas, testing sites were disproportionately located in whiter communities. Millet points to a recent study, released pre-peer review, that found that when testing levels went up in disadvantaged neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Chicago and New York City, so too did the evidence of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on these communities.

A registered nurse draws blood to test for COVID-19 antibodies at Abyssinian Baptist Church in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City on May 14. Churches in low income communities across New York are offering COVID-19 testing to residents.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

A registered nurse draws blood to test for COVID-19 antibodies at Abyssinian Baptist Church in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City on May 14. Churches in low income communities across New York are offering COVID-19 testing to residents.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

Lawmakers have raised concern about the way the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports racial and ethnic data; the agency didn’t report on demographics early on in the crisis, and even now it updates it weekly but with a one- to two-week lag. Democratic senators Patty Murray of Washington and Democratic Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr., of New Jersey called a recent report on demographics the CDC submitted to Congress “woefully inadequate.”

“The U.S. response to COVID-19 has been plagued by insufficient data on the impact of the virus, as well as the federal government’s response to it,” Murray and Pallone wrote in a letter sent May 22 to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. They called on the Trump administration to provide more comprehensive demographic data.

A tailored public health response

Essien says he’s heard concerns from colleagues that by focusing on race and ethnicity in the disease, “some of the empathy for managing and treating is going to go away.”

“If people feel like, ‘Well, this is a them problem and not a me problem… then that may potentially affect the way that people think about the opening up of the country,” he says.

But unless testing and other resources are directed now to communities that need them most, the pandemic will go on for everyone, says Nunez-Smith.

“This is important for everyone’s health and safety,” she says.

Nunez-Smith says race and ethnicity data is necessary for officials to craft tailored public health responses.

For many people, physical distancing is a privilege,” she says. “If you live in a crowded neighborhood or you share a household with many other people, we need to give messaging specific to those conditions. If you need to leave work every day or leave home for work every day, if you need to take public transportation to get to an essential front line job, how can you keep safe?”

A tailored public health response is already happening in Louisiana, where LaVeist says his task force has recently recruited celebrities like Big Freedia, a pioneer of the New Orleans hip-hop subgenre called bounce, to counter misinformation and spread public health messages about COVID-19 to the African-American community.

Given the pandemic’s disparate toll on communities of color, in particular low-income ones, Fernandez and Nunez-Smith say the public health response should include helping to meet basic needs like providing food, wage supports and even temporary housing for people who get sick or exposed to the virus.

“We have to guarantee that if we recommend to someone that they should be in quarantine or they should be in isolation, that they can do so safely and effectively,” Nunez-Smith says.

Nunez-Smith says if you don’t direct resources now to minority communities that need them most, there’s a danger they might be less likely to trust and buy into public health messaging needed to stem the pandemic. Already, polls show widespread distrust of President Trump among African-Americans, and that a majority of them believe the Trump administration’s push to reopen states came only after it became clear that people of color were bearing the brunt of the pandemic.

Fernandez notes that among Latinos, distrust could also hamper efforts to conduct effective contact tracing, because people who are undocumented or in mixed-status families may be reluctant to disclose who they’ve been in contact with.

“This is a terrible time for all of us who do health equity work,” says Fernandez, “partly because this is so predictable and partly because we’re standing here waving our arms saying, ‘Wait, wait. We need help.’ “

Connie Hanzhang Jin, Alice Goldfarb and Selena Simmons-Duffin contributed to this report.