Is China softening its response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- There is a conventional view that China has pursued a stringent and unsustainable zero-COVID policy.

- Despite the official rhetoric that the government will not change its policy stance, it has actually been adjusting and softening it since 2021.

- This is backed up by data from Chinese regions, showing an increasingly less stringent and more targeted response.

Contrary to the conventional view that China has pursued an invariably stringent (and therefore unsustainable) zero-COVID policy, evidence from newly available data on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) reveals a rather different picture at a regional level.

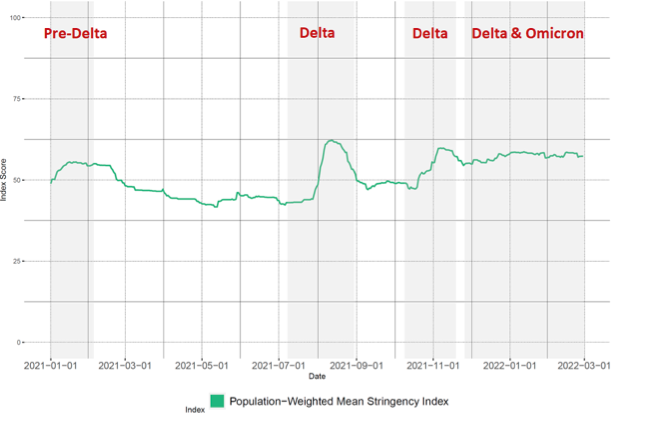

Data show that China’s policy became less stringent and more targeted during the national outbreaks of COVID in 2021, and again in confronting Omicron at the beginning of 2022. The OxCGRT Stringency Index (SI) records the strictness of closure and containment policies, which reduce contacts between people.

Since late October 2021, the average population-weighted SI of Chinese provinces has risen but not exceeded the level of the previous summer wave. The December-January wave saw a new challenge from Omicron, but the overall response stringency was less than that during the first Delta wave in summer 2021.

Figure 1: Comparison of average population-weighted stringency of provinces in China, updated to 28 February 2022.

Image: Data: OxCGRT

Chinese provinces with experience coping with the Delta variant implemented significantly different and less stringent measures in subsequent waves than those lacking experience, as shown in Figure 2 (below). Focusing on 20 provinces with domestic cases in the autumn wave, we divided these provinces into two groups according to whether or not they experienced local outbreaks in the summer.

Figure 2 shows that Group A and Group B shared close mean peak daily domestic cases, namely 12.5 and 12.9, suggesting that these two groups experienced a similar scale of local outbreaks in the autumn wave. However, the mean of peak SI was 64.3 in Group A, while that in Group B was 70.8, meaning that provinces that had experienced an outbreak in the summer showed less stringent responses in subsequent waves.

Moreover, although the means of days with new daily domestic cases were the same in the two groups (around 11 days), the mean of days with SI > 60 was 12.7 in Group A, lower than that in Group B (16.9 days). These differences indicated that provinces with local outbreaks in the summer applied comparatively less stringent policies yet still effectively controlled the spread of the pandemic.

Figure 2: Comparison of provincial response in the autumn wave. Note: Note: Provinces in Group A experienced local outbreaks in the summer, including Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Henan, Beijing, Sichuan, Ningxia, Chongqing, Shandong, Yunnan, Jiangsu, Hubei, and Hunan; provinces in Group B did not experience local outbreaks in the summer, including Heilongjiang, Hebei, Gansu, Shaanxi, Guizhou, Qinghai, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang.

Image: Data source: OxCGRT, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China

The Chinese approach to confronting COVID is becoming increasingly less stringent because Chinese authorities learn from experiences accumulated in previous outbreaks. For example, Henan experienced a severe outbreak in the summer with 41 daily domestic cases at the peak date, and its SI soared to roughly 74.5. In the autumn wave, though Henan’s peak daily domestic cases ranked third in Group A, its SI was only 44.4 on the peak date. This low SI may be a result of the experience gained by the province in the previous local outbreak.

Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, locked down all communities, closed all non-essential places, prohibited all kinds of gathering activities, and suspended public transport operations at the city level after domestic cases were confirmed during the summer outbreak. However, when confronting the autumn wave, it only applied the same measures in a specific town with confirmed cases while allowing people to gather for activities, entertainment venues to open, and public transport to run in other areas.

This finding sends an important message about the future of China’s zero-COVID policy. Despite the official rhetoric that China will not change its policy stance, the country has actually been adjusting and softening it in a de facto way since 2021. It’s true that some cities re-adopted stringent policies when confronting the Omicron wave in March, but we predict that China’s regional governments will adopt more targeted responses after accumulating enough experience tackling Omicron. This adjustment of regional policy stringency based on experience learning may present China a defacto plan of exit from its zero-COVID policy in the long run.

Thomas Hale, Yuxi Zhang, Hui Zhou, Lijun Wang, Zihan Zhang, Zijia Tan, Longmei Deng contributed to this article as co-authors of the underlying working paper.