Study asserts inequality drove COVID-19 transmission in the Mission District

The high rates of COVID-19 in the Mission District can be explained by social and economic disparities, according to an unreviewed paper published on Wednesday.

The preprint, which means the study has not been yet peer-reviewed, highlights new information on the rates of prior infection as well as affirms that COVID-19 has been disproportionately impacting disadvantaged groups.

The study’s findings also showed that asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers are just as able to transmit the virus as those displaying symptoms.

Jon Jacobo, a leader of the Latino Task Force for Covid-19 and a co-author on the new preprint study, was particularly struck by that result. “You can be one hundred percent asymptomatic and still have the same levels [of the virus] as somebody that is symptomatic,” he said. “That should be an eye-opener for people.”

“Especially right now, as the country is going into reopening, and everybody thinks things are good, they’re great,” said Jacobo, “I don’t think we really understand what is actually happening.”

Jacobo said the findings that COVID-19 had been most impactful for those who had to work, was not a surprise. “This is not the great equalizer, as some people have framed it,” he said. “This impacts those that are on the front lines working and people that are most marginalized.”

“It’s hard to take in,” said Jacobo. “It’s folks that are making the ultimate sacrifice in some instances just to put food on the table.”

Over four days in late April, Unidos En Salud, UCSF and the San Francisco Department of Health, administered two tests–a “PCR” test, which determines whether someone is positive, and a serology test, which determines whether someone has been infected in the past and now has antibodies.

The researchers conducted free walk-up testing to all residents and workers in the US census tract 229.01, a 16-square-block section of the Mission District, bordered by Cesar Chavez Street, 23rd, Harrison, and South Van Ness Avenue. The tests were conducted from April 25 to 28 and on the final day, testing was open to residents and workers in several bordering blocks. Additional testing of home-bound residents was conducted in early May.

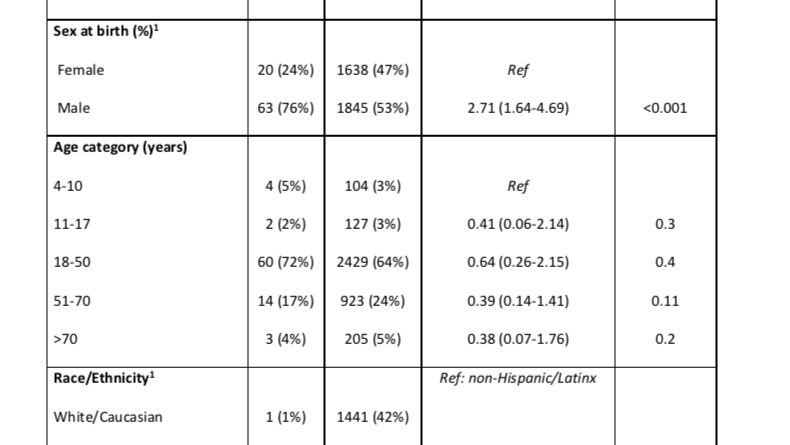

Preliminary results from the initial testing were released in early May, showing that 95 percent of those who tested positive in the Mission District were Latinx, despite only comprising 40 percent of the study’s testing pool.

According to the full report, more recent infections were found primarily among low-income, Latinx people working frontline jobs.

With both the antibody tests and PCR tests, the researchers estimated that 6.1 percent of the residents from the census tract had been infected since the start of the pandemic.

Some hard-hit cities that have conducted similar surveys, such as Los Angeles, had a lower infection estimate at 4.65 percent, Dr. Gabriel Chamie, an associate professor in the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine and lead author on the preprint study wrote in an email. But the Los Angeles study only measured the presence of antibodies, wrote Chamie, which might explain why the Mission study results were higher.

In an April New York study, an estimated 14.9 percent of the state’s population has COVID-19 antibodies.

By comparing the PCR and antibody results from late April, the study estimated that 96 percent of new infections, where the virus is present without antibodies, were in Latinx individuals. Those infected earlier in the pandemic were only somewhat more representative of the Mission’s demographics, with 67 percent Latinx, 16 percent White, and 17 percent other, according to the study.

The prior infections were found more frequently in those ethnically and economically diverse.

The report asserts that low-income workers in frontline jobs could not afford to shelter-in-place and risk losing their income, therefore increasing their chance of recent transmission. Furthermore, the multi-generational and multi-family households common among the Latinx community also furthered the chance of new transmission.

Other risk factors for more recent infections in late April included unemployment and household income of less than $50,000 per year.

Jacobo said that the findings have enforced some of the proposals the city has already undertaken to better support these groups, such as the Right to Recover program, an initiative to provide workers who test positive with two weeks worth of minimum wage funds. Along with that, Jacobo said the findings have also encouraged him to consider other creative ways to help the Latino community.

“It’s still dangerous. The danger has not gone away, there is not a vaccine, this is still very real,” Jacobo said. “We have to try our best to protect ourselves and our loved ones.”