What Happens When the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Ends?

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic was first declared a health emergency by then-Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in January 2020.

Since then, the declaration — which makes more funding and resources available for vaccines, testing and treatment — has been renewed almost a dozen times through the administrations of both Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

The most recent public health emergency, or PHE, is slated to lapse after Wednesday. But ending it could jeopardize the government’s response to the COVID crisis and end Medicare and Medicaid coverage for millions of Americans.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, there have been more than 101 million infections in the US and nearly 1.1 million deaths. With widespread access to vaccines, including the latest booster shots, Americans have gained more protection against severe disease.

Here’s what to know about the public health emergency declaration, including what it does, when it could end and what happens when it does.

For more on COVID-19, find out what we know about the latest variants, how to order more free test kits and how to differentiate coronavirus from the flu.

What is a public health emergency?

Under the Public Health Service Act of 1944, the secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services can determine that a disease outbreak or bioterror attack poses a public health crisis for a period of 90 days at a time. After that, the declaration must be extended.

That public health emergency determination allows the HHS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other government agencies to access funding and increase staffing “to prevent, prepare for, or respond to an infectious disease emergency.”

It also waives certain requirements for Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (aka CHIP) and relaxes restrictions on telemedicine.

Some 20 million people have enrolled in Medicaid since the start of the pandemic, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, an increase of 30% over typical numbers.

When is the COVID-19 public health emergency set to expire?

An emergency was first declared on Jan. 31, 2020, and has been extended 11 times since then. The last renewal was Oct. 13, 2022.

The current public health order is scheduled to expire on Jan. 11, 2023. But the HHS said it would give 60 days’ notice before ending it and no order has been given yet.

The HSS would not address the possible termination or expiration of the emergency. But several Biden administration officials confirmed to Reuters in November that the order would not end this month, citing the possibility of a COVID surge this winter and the need for more time to transition into private coverage.

The White House is aiming to end the public health emergency this spring, Politico reported. A 90-day extension now would mean it would last until early April.

What happens when the public health emergency ends?

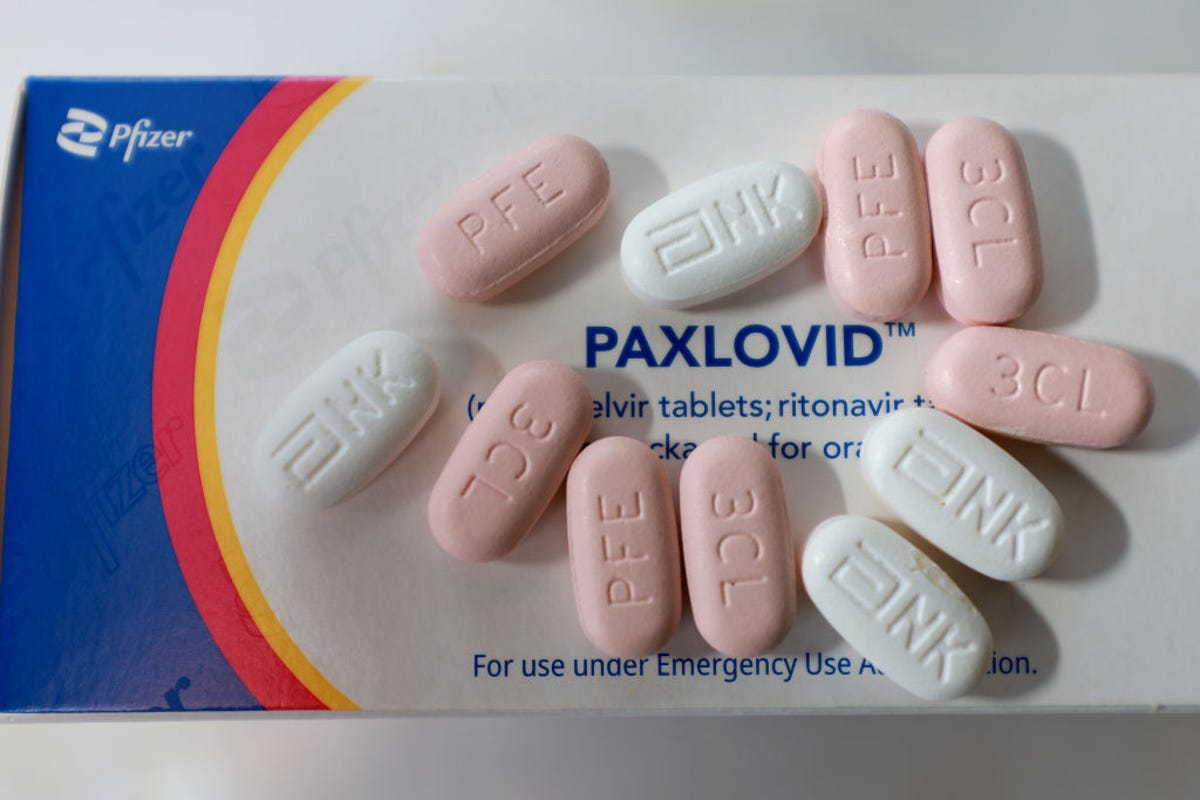

To date, the cost of Paxlovid has been covered by the federal government. That will end when the PHE expires.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

When the declaration lapses, payment for COVID-19 vaccines, testing and treatment would likely become the responsibility of individuals and their health insurance companies.

The retail price of Pfizer’s two-dose COVID vaccine is expected to quadruple from the current government rate, from $30 per shot to between $110 and $130.

Paxlovid, which has been shown to be nearly 90% effective in reducing the risk of severe COVID-19 illness, would also no longer be free. A course of the drug currently costs the US government $530, according to Kaiser Health News, but that’s at a bulk discount. Pfizer, which manufactures Paxlovid, has not said what the retail price would be.

Right now, special waivers for Medicaid and Medicare requirements that have been throughout the pandemic will also come to an end when the public health emergency expires. Without government action, that would cause more than 5 million people to lose health care coverage by 2024, according to management consulting firm OliverWyman.

The debate over renewing the public health emergency

In a November 2022 open letter to Congress, the National Association of Medicaid Directors said “the uncertainty around the PHE is no longer tenable.”

The organization asked lawmakers to provide concrete information on when normal Medicaid coverage would resume, with at least 120 days’ notice.

“The most critical thing Congress can do to ensure a successful unwinding from the PHE is to provide clear dates and funding levels in statute for state Medicaid agencies to reliably plan around,” it said.

That same month, Mark Parkinson, president of the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living, asked HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra to renew the public health emergency past the current Jan. 11 cutoff.

“Coming out of the holiday season, we need to ensure our health care infrastructure can quickly adapt,” Parkinson wrote. “Extending the PHE is critical to ensure states and health care providers, including long-term care providers, have the flexibilities and resources necessary to respond to this ever-evolving pandemic.”

But a month later, 25 Republican governors asked President Biden to end the public health emergency declaration, claiming it’s a financial burden costing states “hundreds of millions of dollars.”

“While the virus will be with us for some time, the emergency phase of the pandemic is behind us,” they wrote.

Many people have returned to employer-sponsored health coverage, the group added, but “states still must still account and pay for their Medicaid enrollment in our non-federal share.”

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.