Boosting Food Sovereignty And Community Growth With Food Forests

In 2021, the United Nations World Food Programme’s Hunger Map estimated that 957 million people across 93 countries did not have enough to eat. Yet, six years earlier, a study by the Global Forest Expert Panel on Forests and Food Security concluded food forests could play a role in complementing agricultural production.

How Food Forests Work

Key to protecting biodiversity and mitigating climate change, a forest’s contribution to alleviating hunger is not well known or fully understood by many. Yet, forested gardens have produced enough to feed entire communities for thousands of years. For example, in Morocco, the food forest of Inraren is over 2,000 years old and still produces edibles.

Unlike mass-produced crops, food forests use permaculture practices focused on small-scale food production. This model is ideal for small towns, remote communities with limited access to fresh produce, and urban neighbourhoods. The forests adhere to what Bill Mollison, the “Father of Permaculture,” described as the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive systems with natural ecosystems’ diversity, stability, and resilience. The forests harmoniously integrate into the landscape with people, providing food, energy, and shelter in sustainable ways.

Unlike traditional community garden plots managed by an individual or small group, food forests are three-dimensional edible arboretums often set within a communal landscape. This invites a collective approach to design, maintenance, and food sharing that refers to when communities worked together and weren’t dependent upon imported goods or unreliable supply chains.

In the Browns Mill region of southeast Atlanta, the city manages a growing 2,800-hectare food forest that invites the public to take what they need at no cost. In Spain, the edible forest of Juan Anton Mora was established 20 years ago with an open-door policy. In Canada, these edible gardens of Eden are being planted as hubs of learning and community and provide hope that food equity everywhere is possible.

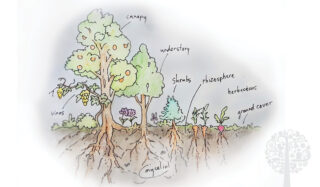

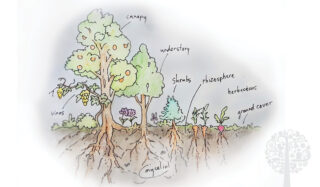

The Seven Natural Layers of a Food Forest

A food forest mimics natural patterns, extending vertically and horizontally with seven distinctive layers. The overstory, or canopy, is created by tall fruit and nut-producing trees. A layer of dwarf fruit trees follows, and berry-producing shrubs come next. Herbaceous plants transition to a layer of edible ground cover that functions as living mulch. Below the soil surface, root vegetables grow in the rhizosphere. Finally, a vertical layer of vines and climbing plants grow up the tall tree trunks, seeking the sun. If mushrooms are grown, they are considered a separate mycelial eighth layer.

Plants are predominantly perennial or self-seeding, returning each growing season independently. Once established, nut-producing trees live for hundreds of years, and berry bushes for a decade or more. In a food forest, no irrigation or fertilizer is used. Natural drainage, groundwater, and precipitation supply water needs, helping balance maintenance and costs.

Fields are often left fallow after harvesting annually grown crops, allowing the soil to rest and rejuvenate. The same does not occur in a food forest. If a plant fails, it can decompose naturally, releasing bacteria and fungi that add to fertilization and soil health. The diversity of what is planted means less competition for the same resource. Species that require more water to grow are likely to be placed near natural drainage areas at the bottom of a slope or close to a stream bed, while more drought-tolerant plants are grown elsewhere.

Fredericton’s Botanic Garden

Fredericton’s Botanic Garden food forest started as a small orchard in New Brunswick, Canada. Simi Usvyatsov, a volunteer at the garden, knew of food forests in other parts of the province and saw the potential of what the orchard could become. Working with the City, the Atlantic Permaculture Network, Fredericton Food Rescue, and the Botanic Garden Association, the project received a grant of $5,000. Last fall, an overstory layer of chestnut, hazelnut, and butternut trees was planted, forming three sides of a rectangle that will function as a sun trap for a grape arbor. The shrub layer will include Nanking cherry, highbush cranberry, gooseberry, and haskap.

Stephen Heard, a biology professor at the University of New Brunswick and President of the Fredericton Botanic Garden Association, sees the project as a learning opportunity more than a place to harvest and formally distribute food. He likes the idea of people being able to pick and gather what they want when visiting the forest. Still, he says the more exciting part of the project is the potential to educate visitors about permaculture and locally sustainable food production.

Vancouver Urban Forest Foundation (VUFF)

Imagine orchards encircled with salmon, salal, and oso berry bushes native to British Columbia’s south coast. A canopy of oak and chestnut trees relieves fiddlehead ferns from the hot sun. Rhubarb lines pathways, and fields of wild asparagus and sunflowers attract insect pollinators, bees, and butterflies; this is VUFF’s vision for every park throughout the city.

In alignment with Vancouver Park Board’s Local Food System Action Plan, which encourages strengthening food networks within city neighborhoods, Marie-Pierre Bilodeau, Operations Coordinator for VUFF, says they are cultivating a sharing ideology. VUFF advocates shared decision-making concerning food sovereignty, what is planted, and how it’s managed and harvested, engaging with community members, groups, and neighborhood houses. People will be able to come and harvest freely. Volunteer groups will manage tasks, maintenance, and crops with the overall goal of serving the community.

Saskatchewan

Muskeg Lake Cree First Nation in northern Saskatchewan has struggled with the availability of fresh produce. Shipping costs are expensive, which results in higher food prices for what is available. When asked how the community saw a food-secure future, the collective answer was to rebuild connections to the land and focus on traditional growing practices that sustained them for thousands of years.

In 2018, the community planted a 2.5-acre food forest, collaborating with the non-profit Feed the Children. Berry harvests are used for public events, and by 2025, fruit and nut trees will be producing enough for the entire community to enjoy regularly. Ground cherries and gooseberries form the shrub layer. Mints, herbs, red and purple clover, rye, and other grasses create a lawn that enriches the soil and chokes weeds.

Steven Wigg, permaculturist and Food Security and Climate Change Supervisor at Muskeg Lake, says a small, dedicated community with a few acres of land could soon be self-reliant for their fruit, herbs, starch, and a large portion of their vegetables.

Food forests are altering how communities view food production. By planting and growing according to the needs of the natural world, they remind us that if we just let it, our fragile planet will happily and successfully supply all we ask of it.

Sources:

Center for Disaster Protection: disasterprotection.org/lookoutletter

2021 is going to be a bad year for world hunger | United Nations

THE GARDEN | fbga-home (frederictonbotanicgarden.com)

Indigenous Food Forests – Canadian Feed The Children

What is a Food Forest? – Project Food Forest

Food Forests — edible landscapes that do more than feed us – Farm to Cafeteria Canada

Muskeg Lake Cree Nation community food forest helps connections, knowledge grow | CBC News

The 12 Permaculture Design Principles (permacultureprinciples.com)

Could these ancient food forests help feed the world? | Adventure.com

Definition of Permaculture | Living Permaculture (livingpermaculturepnw.com)

Food Forests: – OALA | The Ontario Association of Landscape Architects

Food Forests – An Exploration (part 1) – The Permaculture Research Institute (permaculturenews.org)