Lactic Acid Fermentation A Tasty And Nutritious Science Experiment

Fermentation is one of the oldest methods of food preservation. Since the stone age, it has been used worldwide to extend the shelf life of a wide range of foodstuffs. Families around the globe followed fermentation-based recipes; when home refrigeration became common in the 1950s, we forgot knowledge of these ancient methods.

One fermenting method, in particular, is very close to my heart because as a young Pole, I was brought up on many fermented foods, whether I liked them or not. In a country where gherkins and sauerkraut are so popular that you can buy them in any corner shop, you learn to love them. This most common process followed in Poland is called Lacto-fermentation, and recent studies have shown that there’s a lot more to it than just the tangy flavor. With the fermentation craze hitting social media and workshops popping up on all the platforms, let’s get into what the whole fuss is about.

What is Lacto-Fermentation?

Lacto-fermentation is a type of fermentation in which lactic-acid-producing bacteria create an unfriendly environment to other kinds of food-rotting organisms, therefore protecting the food from spoiling. Lactic acid is formed when sugar is broken down in an anaerobic environment, leaving behind much simpler compounds. It was first identified in milk that contains sugar and lactose, hence the name lactic acid.

Lacto-fermentation often produces carbon dioxide as a side product, making the foods fizzy, hence the bubbles in kefir or a nicely proofed sourdough. Kefir, cheese, yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchi, and various vegetables are the most popular fermented foods worldwide, but the list doesn’t stop there – far from it. There are also less well-known ones, such as Turkish Shalgam (fermented carrot and turnip juice) or Ethiopian Injera, a fermented sourdough flatbread made from teff, a natural, gluten-free ancient grain.

The Benefits

Nowadays, there’s much discussion about ‘friendly’ bacteria, which offer health benefits such as better digestive health or decreased anxiety. Officially called probiotics, these bacteria and yeasts dominate our gut and crowd out the ‘bad’ bacteria, which can cause anything from mild bloating to illnesses like IBS or Crohn’s disease. By acting positively on the intestinal microflora, probiotics strengthen the protective barrier and help fight infections. Considering that around 70% of our immune system is based on our gut, digestive health is key to our overall well-being.

Despite humans drinking fermented milk for thousands of years, detailed knowledge of probiotics wasn’t available until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Led by observations of people drinking fermented yoghurt in the Caucasian mountains, Russian scientist Elie Metchnikoff drew some conclusions, followed by studies at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, which contributed to him winning a Nobel prize for immune research in 1908.

Scientists and health advocates rave about various benefits fermented foods offer humans, from glowing skin to mood improvement. Unfortunately, gut bacteria can cross the blood-brain barrier and cause brain inflammation – also known as depression. If you have ever tried cutting sugar from your diet then sat down to relax in the evening, you’ll know the feeling of the sugar craving hitting hard. Suddenly, you remember that there’s a stash of biscuits in the cupboard; this is the ‘bad’ gut bacteria screaming in fear of dying if it’s not fed some sugar, begging you to go and eat that biscuit. It takes two weeks of exchanging your gut microflora, so a cold turkey approach to simple sugars doesn’t mean eternal torture.

How Lactic Acid Fermentation Works

As the vegetables and fruits are pickled, the initial sugar content decreases, lowering the number of calories. In addition, high fiber content increases the feeling of fullness when eaten, and the naturally low pH supports the stomach, which performs better in acidic conditions. All this makes fizzy foods easier to digest and increases their nutritional value.

High levels of vitamins A, C, and E combined with powerful antioxidants bring claims of counteracting aging of the body and reducing cancer risks. Contrary to popular belief, fermentable foods do not contain more vitamin C than fresh vegetables and fruits. The process of fermentation stabilizes vitamin C and prevents it from breaking down. Under normal conditions, it is one of the most sensitive vitamins that perishes under heat treatment, light, or oxygen.

It’s worth remembering that not all the bacteria in Lacto-fermentation are sure to be good ones. Sometimes the ‘baddies,’ such as lactococcus or leuconostoc, can be harmful or pathogenic. These cause bad flavors and smells in dairy products, sour and cloudy beer (although, if you’re a fan of milky IPAs and sours, you can use this to positive effect), and turn juices slimy. There are a few critical rules to follow, and close observation of the process is crucial to fermenting success. It’s safe to say that any signs of mold mean you have to discard and try again.

Now that you know a few of the health benefits, why not try making your own? You can ferment pretty much anything, from tomatoes, cauliflowers, carrots, cabbage, and cucumbers to whole apples and pineapple (yes, I, too, thought that was crazy until I made a delicious hot sauce with pineapple, garlic, onion, and ginger).

Kvass Recipe

One of the most common ferments in Polish kitchens is traditional beetroot kvass, a healthy probiotic drink rich in vitamins A, C, and E, and exceptionally rich in B-vitamins, potassium, and folic acid. Drinking beet kvass helps with getting over a cold thanks to the natural antibiotic properties of garlic. It is used as a neat drink, served either cold or warm, diluted in some warm water, or turned into a soup called barszcz (pronounced ‘barsh-ch’), traditionally served on Polish Christmas eve. Once ready, you should store it in the fridge; use the leftover beets in various dishes such as potato salad, omelets, or savory pancakes, to name a few. As fermented foods are full of life, any heat treatment like cooking will kill them off, so always try them raw or in mildly warm drinks, never boiling water.

What You’ll Need:

- A clean jar

- Salt

- Water

- Beetroot

- Garlic

- Herbs of your choice.

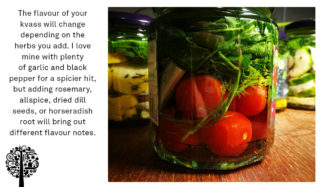

As with all quality food, ingredients matter. Use rock salt or quality sea salt, filtered water (unless your tap water is excellent quality), and fresh beetroot. The flavor of your kvass will change depending on the herbs you add. I love mine with plenty of garlic and black pepper for a spicier hit, but adding rosemary, allspice, dried dill seeds, or horseradish root will bring out different flavor notes.

Slice, dice, or grate enough beetroot to loosely fill your jar; add the whole garlic cloves (more is better; I like about six cloves per liter of liquid), herbs and spices.

Mix one flat tablespoon of salt in a liter of water to create the brine and fill the jar, so the brine completely covers the beets. You can weigh it down with a glass ramekin or check it daily and make sure nothing sticks up above the brine, as this may cause mold and spoil your experiment.

You can either close the jar’s lid or cover it with a cloth. You may see a thin film form on top, but as long as it doesn’t have hairy blobs of mold on it, don’t worry. The film you see is Kahm Yeast, which is harmless and indicates that the sugars have depleted.

Depending on your jar size, your kvass should be ready in around seven to ten days. The brine will turn a little thicker, and the color will be a beautiful deep purple. The flavor should be rich and salty-sweet with a slightly fizzy feeling.

Enjoy!