No Water, No Problem! Regenerating Dry Land Without Irrigation

With the climate crisis on minds worldwide, many have turned to water conservation techniques in the garden. Of course, any effort to save a precious natural resource is valid, from xeriscaping to collecting rainwater. But how do you grow if there’s no potential for irrigation? For many, the mere idea of no water is enough to send them running. But not for the team at Drylands Agroecology Research (DAR). Based in Colorado, the organization is up for the environmental challenge, transforming dry, marginalized landscapes into lush ecosystems – without water.

Spearheaded by Nick DiDomenico and Marissa Pulaski, DAR designs and implements natural infrastructure to create pathways and catchment systems for water from existing precipitation. In a climate that only gets about 16 inches of rainfall a year, that’s a tall order, but DAR is proving that achieving lively landscapes in semi-arid conditions is possible, one farm at a time.

Regenerating Dry Land at Elk Run Farm

It all started in 2015 when DAR began managing Elk Run Farm, a 15-acre parcel of degraded land in the Colorado foothills. A former cattle ranch, the sloped property was arid and had little vegetation thanks to years of overgrazing. Refusing to accept that the land was useless, DiDomenico got to work, following permaculture principles to regenerate the fields. Pigs, chickens, and sheep helped build topsoil and bring new life to the pastures while an exotic forest garden was planted. Largescale earthworks called contour swales were built to manage the water flow on the property. The swales are ideal for hillsides, catching and retaining every drop of water and resulting in moist pockets perfect for planting trees.

“People thought they were nuts,” explains Amy Scanes-Wolfe, Community Outreach Director at DAR. “They knew they’d only be able to irrigate [the trees] once, which is the day they were planted, and then there would never be water again.”

Despite widespread doubts, DAR set about planting over 1,000 trees, including apple and pear trees, mulberries, plums, and nurse plants to help fix nitrogen in the soil. The trees were planted about a foot and a half apart, assuming most would die. But that didn’t happen. Several years later, DAR is tracking a 79% survival rate on the trees, an incredible victory, and proof that the contour swales are collecting enough water to sustain an ecosystem. Meanwhile, the new microclimate helps cool things down.

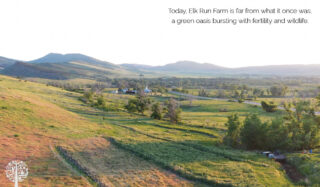

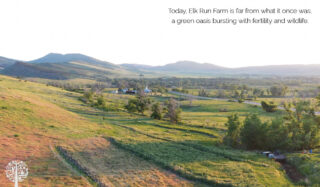

Today, Elk Run Farm is far from what it once was, a green oasis bursting with fertility and wildlife. As the pilot research project, DAR continues to collect data from the farm as it refines its selection of perennial crops, grain crops, and forest garden systems. But while it takes time for natural systems to establish, the beauty is that once they do, most of the hard work is over.

“We put a lot of effort into getting that system going, and then if we do nothing at all, it will keep regenerating,” explains Scanes-Wolfe. “So, as those trees grow, they create this cooler, moister microclimate and habitat, and birds are coming in and pooping seeds. Between those swales, we practice regenerative grazing with either cattle or sheep.”

Seeing is believing, and after witnessing the wild transformation at Elk Run Farm, other farms are knocking on DAR’s door, looking for help in their land regeneration and growing ventures.

Yellow Barn Farm Land Regeneration Project

Last fall, DAR broke ground at Yellow Barn Farm, a former large-scale equestrian center in Longmont, CO, that was once home to over 50 horses. Windy and exposed, the property spans 60 acres, 50 of which have no potential for irrigation. The farm had fallen victim to a monoculture system and over- and undergrazing, and in 2020, the devastating Calwood Fire swept through the area, scorching the surrounding land.

The owners of Yellow Barn want to regenerate the farm and grow high-quality food on a small scale, eventually setting up a CSA. The property also serves as a community hub for sustainability education; anyone interested in land rejuvenation and carbon sequestration is welcome to come and witness DAR and other environmental organizations work their magic.

“We are trying to create a new type of ecosystem,” says Scanes-Wolfe. “It’s not native, but it feeds people and has all the benefits of a wild ecosystem, like habitat and carbon.”

With the help of a $100K grant from the Woodard & Curran Foundation, DAR has created 17 contour swales across the 50 acres. Cattle move between the swales following rotational grazing, and this spring, 6,000 fruit and nurse trees are being planted where the water has accumulated over the winter. While the swales are always filled with mulch and compost for water retention and to help build fertility, this time, DAR has experimented by layering oyster mushroom mycelium into two-thirds of the trenches. The team will monitor how this impacts tree health, but initial research suggests the mycelium will boost moisture retention by about two or three times.

“It’s fascinating to see! It’s already completely colonized,” says Scanes-Wolfe. “We were walking around seeding one of the berms the other day, and there was this web of white mycelium across the top of the mulch. If lucky, we might even get mushrooms out of the system!”

Escaping the destructive ways of monoculture, DAR is diversifying the grasslands and using three different seed mixes, including native grasses, wildflowers, and traditional forage grasses for cattle.

“We hope that whatever we seed there will make its way into the pasture below, so this is our chance to put some diversity in the seed bank so that as the cattle come through, it germinates,” explains Scanes-Wolfe.

The Solution to Regenerate Yellow Barn Farm

Volunteers and corporate groups are helping with this spring’s tree planting, and for DAR, this is where the fun truly begins. With agriculture being a massive driver of the current climate crisis, planting trees and building soil is primarily believed to be the solution. While the trees may not go into the world’s greatest soil, they will help build it over time. They’ll also be removing CO2 from the air, and a grant from Boulder County will help DAR quantify the carbon being sequestered in the system at Yellow Barn Farm.

Ultimately, DAR strives to avoid the band-aid solutions we often see regarding environmental repair. For example, rather than focusing on reducing how much water we use, DAR views its mission more as developing the landscape’s capacity to hold water so that when it does rain or snow, the moisture stays in the ground.

People beyond Yellow Barn Farm are taking notice. DAR receives interest worldwide, including from a farmer in Kenya who recently reached out for advice on regenerating dry farmland. Scanes-Wolfe says the current project at Yellow Barn Farm is helping DAR develop a training system so the organization can consult on other projects and educate on how to read landscapes and understand how to regenerate them so they can thrive.

“We are designing systems that sequester carbon but also support biodiversity, restore hydrological cycles, and feed humans,” she says. “[The goal] is to create something that actually solves a lot of problems and gets to the root of what’s going on.”

As the world copes with more environmental disasters such as wildfires, drought, and erratic weather patterns, DAR is a beacon of hope, restoring, repairing, and regenerating dry and degraded land in Colorado using natural systems. Nobody said it would be easy, but someone’s got to do it, and DAR is happy to lead the way.