NCC: Land Lines – Remembering his cedar canoe

My grandfather’s canoe, his pride and joy. Our neighbours out for a paddle in the canoe (Photo courtesy of Asha Swann/NCC intern)

The cedar canoe hanging from my grandparents’ garage roof stands out for good reason.

A dusty photo album in the basement with “1993” scrawled in my grandmother’s cursive tells me that this canoe is older than I am, though it could have been made yesterday. My grandmother filled every photo album in sight, taking pictures of the canoe and everything else in sight. While we stand in the kitchen flipping through its pages, she connects the dots that I was too young to remember.

My grandfather’s hearing went long before his memory. I can distinctly place myself as a child, sitting on my grandparents’ dock in one of British Columbia’s beautiful interior lakes, with my teeny legs swinging, asking him about the flurry of minnows in the water below. His response was always the same: “What?” I’d yell, “Look at all the minnows!” to which he would always echo with a gruff, “No need to shout! You’ll scare all the fish.”

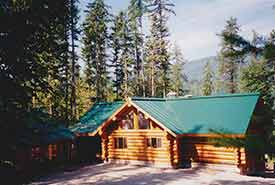

My grandparents’ log house (Photo by Asha Swann/NCC intern)

Though he now prefers the comfort of birdwatching with binoculars on the couch to fishing at the crack of dawn, my grandfather has always been a man who was ready to be outside. Beginning in his early 70s, for 10 years he built a gorgeous log house, backing onto Mara Lake. What seemed to be a huge ocean to my eight-year-old brain was actually a rather remote lake in the middle of BC’s Okanagan region. He soon added to building of this house by adding an adjacent (and matching) cottage. And what good is a lakeside cottage without a canoe? Naturally, only a hand-built cedar canoe would suffice. Asking my grandfather to instead buy a plastic canoe from Canadian Tire would be nothing short of a slap in the face.

His cedar canoe was his pride and joy. I always believed that if they made glass cases big enough, he would absolutely put it on display, turning the basement into an exhibit like at The MoMa. Form an orderly line down the stairs, and, please, no flash photography.

My grandmother jokes that this canoe has seen more time on land than in the water, and I think thatt may be true. It’s been hauled across the country more times than I can count, my grandfather insisting that his hard work get recognized on every road trip, strapping it to the roof of the car. I don’t have to wonder if the canoe has seen more of Canada than I have; I already know it’s true.

Grandfather and I, talking through the glass of the window (Photo courtesy of Asha Swann/NCC intern)

After the log house, the cottage and the cedar canoe were built, my grandfather was not ready to stop. Two decades of hard work had passed, and rather than sit and enjoy the fruits of his labour, he was ready for the next project. Logically, the only way my grandparents could enjoy this huge wooded property was to start a bed and breakfast.

The cedar canoe and the log house were two sides of the same coin. All guests staying at my grandparents’ B&B would marvel at this beautiful boat in the driveway, decorated with traditional Haida First Nation art that the northwest coast is known for. My grandmother fondly remembers guests coming from as far away as Spain and Germany almost begging to take the canoe out on the water that it was just inches away from.

To speak in my grandfather’s canoe was to speak from the heart. Conversations that began in the bow of my grandfather’s canoe seemed to carry through the years, long after my grandparents traded BC for the Ontario suburbs.

My grandparents and I have been living in Ottawa for 14 years. The cedar canoe now hangs in the garage there, thousands of kilometres from the Okanagan. Its spot next to the log house is permanently etched into my mind. I don’t know if my grandfather consciously decided that building the canoe would be his last big project, but as he reaches nearly 90 years of age, I like to imagine what else he could have built if there was more time. Two canoes? Perhaps a desk?

My grandfather with me when I was a toddler (Photo courtesy of Asha Swann/NCC intern)

Every childhood memory I have of him is outside. My grandmother tells me that before I could talk, I would pitter-patter over to the both of them with my shoes in hand, silently saying I was ready to go on a walk. Anywhere outside was good enough for me. I was always more than happy to be shivering at sunrise while my grandfather cast a fishing line off the dock.

I consider asking my grandmother what will happen to the canoe, even though I know she doesn’t have an answer. Instead, I ask her if she remembers that one winter at the log house, the first white Christmas I’d known. She reaches for another album: 2001.